Reimagining Khipus as Musical Notation: Mathematics and Storytelling

Growing up in Cusco, Peru—the Inca capital—I learned about khipus from a young age. Like many Peruvian students, I was told that the Incas and their predecessors did not learn to write or read. As a kid, surrounded by Cusco’s extraordinary Inca architecture, this never made sense to me. Fortunately, recent studies have reshaped our understanding of how Pre-Columbian societies communicated through unique notation systems. Khipus, in particular, challenge colonialist perspectives that dismiss the capacity of Pre-Columbian civilizations to generate sophisticated mathematical processes and notation systems. Eventually, this led me to question how khipus were—and still are—analyzed, beginning with the fundamental question: "How do we read?"

This mindset has been central to my research, where I argue that technology—especially in music—reflects the intellectual, emotional, and spiritual dimensions of humanity.[1] What circumstances led some cultures to develop two-dimensional systems? And how did the khipu emerge as a unique three-dimensional notation system? The challenge of understanding khipus deepened when their makers and readers—the khipukamayuq—broadly disappeared during colonization. In some cases, khipus were maintained to keep records in the colony; however, some khipus were deemed "demonic" devices that hindered evangelization in the Americas.[2] This reveals that khipus were not just functional tools; they also could become objects imbued with profound spiritual significance.

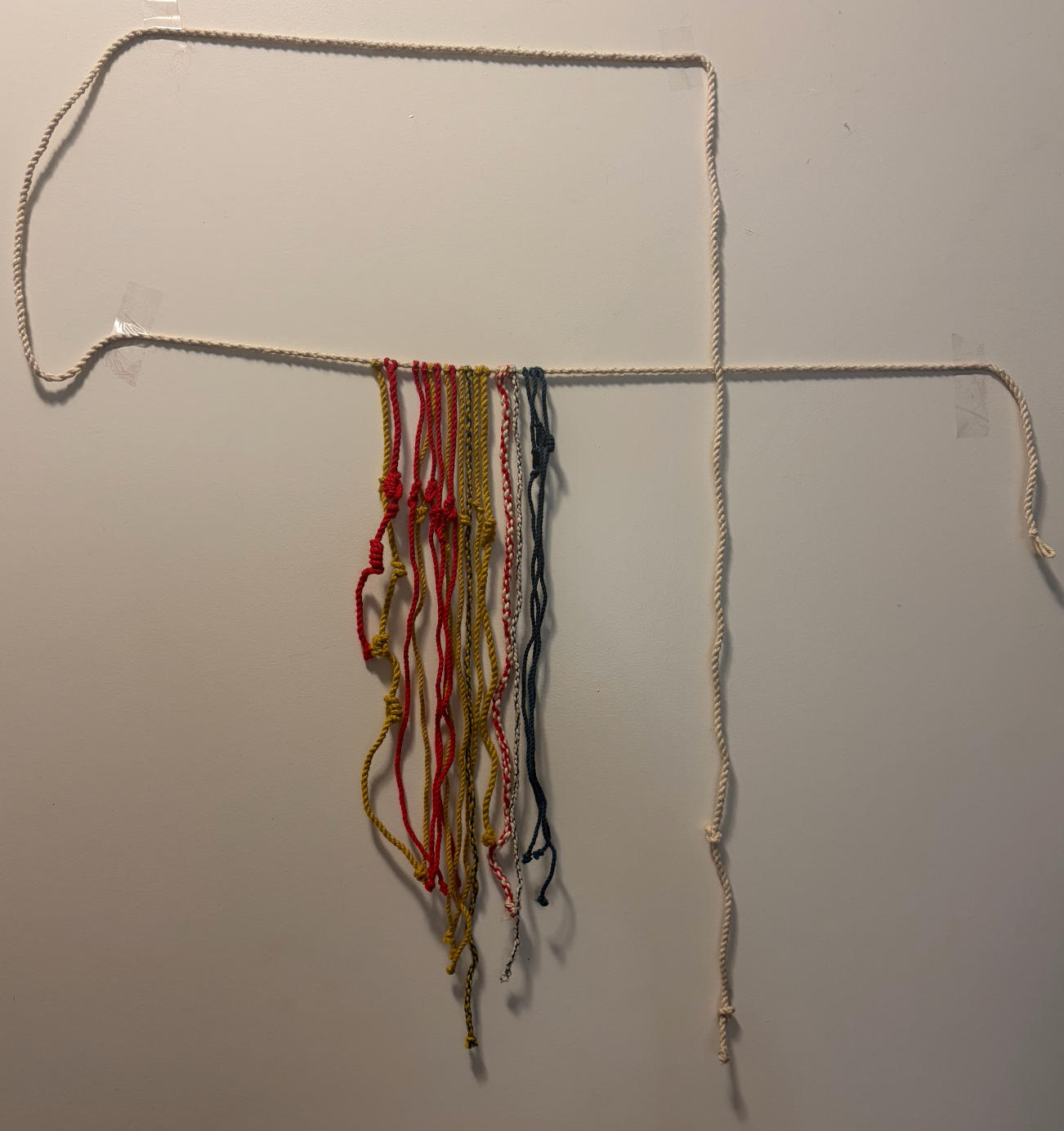

Khipu for KIPU 2b, for open instrumentation.

Khipu for KIPU 2b, for open instrumentation.

Despite not knowing how to make or read khipus, I began exploring their potential as a musical notation system. I felt inspired by the fact that my father’s mother was a skilled traditional weaver, a form of knowledge I was not able to learn, but one I somehow sought to reconnect with and honor. Marcia and Robert Ascher’s (1981) Mathematics of the Incas: Code of the Quipu proved useful in learning techniques to make the strings.[3] Subsequently, since music integrates both mathematical reasoning and storytelling, I found some connections in the process of adapting Western music notation to khipus. The Western system relies on concepts of up and down, left and right, to determine the meaning of its semantic elements. I soon recognized the possibilities for developing micro and macro structures, similar to a Western musical score, using the fractal, self-contained nature of khipus.

I then learned about Johan Sebastian Bach's 14 Canons—musical counterpoint exercises rather than compositions. His works revealed to me the possibility of encoding multiple layers of information within the same musical structure. Bach's canons use one four-measure melody explored through 14 variations: upside-down, in slow/fast motion, backwards, and in complex combinations.[4] I found that this relationship with direction could be represented on a single string, since, like Western music, khipu strings possess a kind of linearity defined by a beginning and an end. This linearity persists regardless of how the khipu is held, allowing for the development of microstructures.

I then adapted the Inca numerical system of knots to indicate numerals from 1 to 10, enabling representation of pitch and duration—the horizontal and vertical aspects of Western music notation. For macro structures, I drew inspiration from sonata form—a structural tool in classical music emphasizing introduction, development, and conclusion. This means of design reflects rhetorical principles used in both literature and music. The linear nature of khipus thus allows me to "map out" a musical piece’s structure from beginning to end.

Khipu for PoemRite 4 - “A Song on Strings and Knots” for voice and electronics.

Khipu for PoemRite 4 - “A Song on Strings and Knots” for voice and electronics.

My intention is to use khipus in their original form as authentically as possible, replicating the process of the khipukamayuq. I therefore focus on khipus as a technology deserving attention in its ancestral form, though I applaud other artists who incorporate modern technologies into contemporary approaches.[5] I embrace the ancestral nature of khipus: strings and knots.

To illustrate this, I present three works. The first work, KIPU 2b, is performed using traditional Peruvian instruments, and it demonstrates the micro and macro structural possibilities of notating music in khipus. An explanation of this notation can be found in an article on my website. The second work, Astrolatry, is designed for four singers, each holding a khipu to read from. For this performance, the singers did not learn to read each individual note due to time constraints, but the khipu helped them recognize the macro structure and maintain group synchronization. This made me reflect on khipus as mnemonic tools, similar to jazz charts that maintain macro structure while allowing microstructural improvisation. I applied this idea in my third work: PoemRite 4 - “A Song on Strings and Knots”

Through my work, I have also explored texture—a paramount concept in contemporary music—using strings made of different materials, like nylon and elastic, to portray varied musical textures. The color of a given string, then, adds another informational layer applicable to both micro and macro structures. This is demonstrated and explained in the article mentioned above.

Through this text, I share the concepts and principles of my approach to khipus, which aims to honor the intellectual legacy of the khipukamayuq by reimagining khipus for artistic creation. Given current historical limitations, I offer this artistic possibility as a way of contributing to research on deciphering khipus by providing a perspective from the experience of integrating ancestral khipu usage into modern art and music.

Khipu for Astrolatry, for soprano, alto, tenor, and bass voice.

Khipu for Astrolatry, for soprano, alto, tenor, and bass voice.

This concept is informed by Marshall McLuhan's (1964) Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, where he states that “the medium is the message,”shaping my approach to understand how music technology is a medium and a message. ↩︎

For instance, Garcilaso de la Vega’s (1609) Comentarios reales de los Incas and Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala’s (1615) Nueva corónica y buen gobierno describe the role of the khipukamayuq and reference the loss of khipu knowledge during colonization. This narrative can be contrasted with—and complemented by—Brokaw’s (2010) A History of the Khipu, which points to instances of khipus being adapted and preserved. ↩︎

The second chapter of this book illustrates on twisting techniques, using spindles, which was the same technique my grandmother used. However, in my latest khipu, I adapted a fan engine as a device to twist the strings, which allows faster results. This particular experience made me reflect of another reality in which the khipus meet industrialization, which opens other discussions proposed from an artistic standpoint. ↩︎

In Chaper 12, of Christoph Wolff's (2014) Johann Sebastian Bach: The Learned Musician, he explains about The Art of Fugue and discusses the 14 Canons and their discovery in Bach's personal Goldberg Variations copy. This is brilliantly illustrated in this Youtube video titled BWV 1087 - 14 Canons. ↩︎

In 2021, Paola Torres Nuñez del Prado gathered several artists converging with the khipus in the arts. This allowed me to know about the work of several artists around the world. The documentation of this virtual encounter is available in her website. From this group, I was able to meet Patricia Cadavid in UCLA at the presentation of her Electronic_Khipu at the Fowler Museum at UCLA in May of 2025. ↩︎

Comments ()