Have We Found the “Rosetta Khipus”?

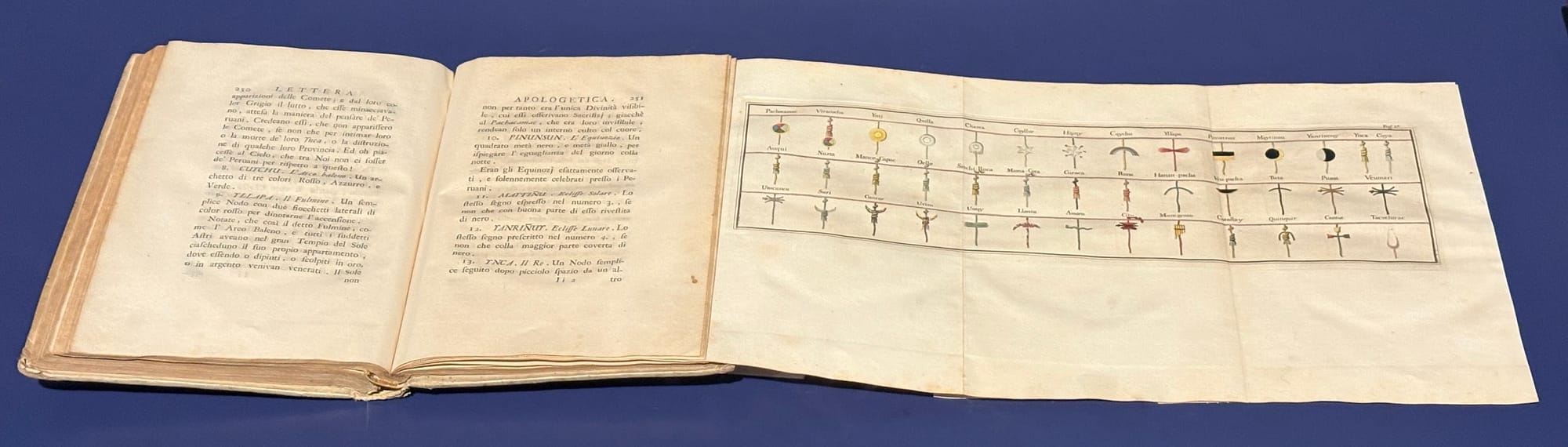

In his 1750 Lettera apologetica[1] Raimondo di Sangro imagined a khipu sign dictionary and subsequent knot alphabet in which words and letters were created through different combinations of knots, colors, and attached objects (Figure 1). I have often dreamt of having something similar myself, though one which actually reflects the structures and data encoded in extant Inka-style khipus: a full khipu dictionary, filled with page after page of khipu signs and their meanings translated into a language we can understand today. While I still hope such a manuscript might one day surface—perhaps in a dusty archive in Seville or Lima—for now we have to rely on other ways of advancing khipu decipherment.

Figure 1. A copy of Raimondo di Sangro’s Lettera apologetica on display in the Museo de Arte de Lima (MALI) , Peru, in July of 2025 (Photo by Mackinley FitzPatrick).

If we cannot locate a one-to-one khipu sign alphabet or dictionary, the next best option is to identify individual khipu biscripts: khipu-document matches in which both media record the same information. In another blog post, “Can We Use AI for Khipu Decipherment?,” we discuss the importance of finding a biscript for making real progress on any undeciphered system. The most famous ancient biscript is, of course, the Rosetta Stone, the stele bearing the same decree written in hieroglyphs, Demotic, and Ancient Greek. At the time of its discovery, no one could read hieroglyphs, but scholars could read Greek, thus opening the path to decipherment.

Therefore, one of the most frequent questions I get from both academics and the public is whether anything comparable to the Rosetta Stone exists for khipus. To the excitement, and disappointment, of nearly every audience I speak to, the answer is both yes and no.

We know of several extant khipu boards, or wooden tablets with attached cords and accompanying lists of names. While these hybrid objects show how khipu technology persisted and adapted under Spanish rule, their cords and written text work together rather than duplicating information.[2] Neither the cord or text can stand alone the way the Rosetta Stone’s three inscriptions do.

We also have pages and pages of Spanish court records that contain transcriptions of now-lost khipus.[3][4] However, while these so-called “paper khipus”[5] help reveal the kinds of data khipus once carried, without the original khipus themselves, they reveal very little about how that information was actually encoded.

Finally, we have some recent ethnographic transcriptions of modern herding khipus,[6][7] along with the khipus themselves collected by anthropologists. Again, while these are useful, their structures often differ significantly from Inka-period examples.

So do we have any khipu-document matches for Inka-style khipus? Possibly—one likely case is known: a potential match between a 1670 Spanish colonial document and a set of six Inka-style khipus from the Santa Valley, Peru.

The Santa Valley Khipus

In 2011, similarities were noticed between six khipus (KH0323, KH0324, KH0325, KH0326, KH0327, and KH0328) reportedly from the Santa Valley, Peru, and a 1670 Spanish colonial revisita from the same region. The document pertains to the Recuay ethnic group, who were resettled to the town of San Pedro de Corongo in the Santa Valley.[8] The document states that each of the local tributaries were required to pay a specific amount of tribute to the Spanish crown. After discussing the tribute owed, the revisita includes a padrón (registry/census) which lists the names of the local tributaries (tax payers), with each name sorted into one of six distinct pachacas, or traditional Andean kinship units more commonly known as ayllus. Perhaps most importantly, the revisita states that, after the tribute owed had been announced to the local people, all of the information should be put into khipu(s) (“lo ponga por quipo”).[9]

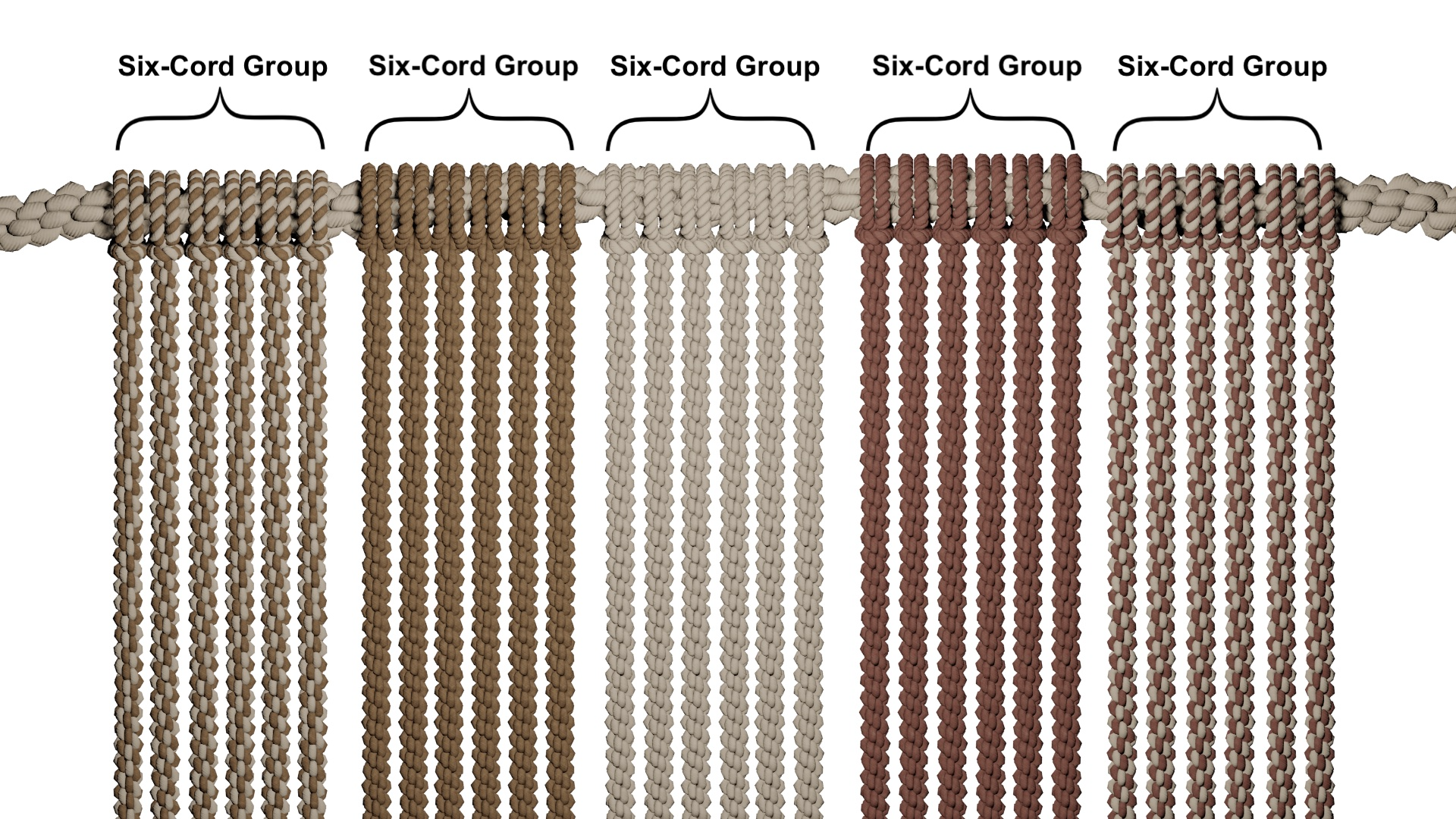

Using these three key pieces of information—the total amount of tribute owed, the list of named tributaries, and the mention of khipu(s) recording this information—Urton suggested that the six Santa Valley khipus may be the ones referenced by the 1670 revisita.[10] He initially proposed two key arguments to support this hypothesis: (1) the organization of the Santa Valley khipus into 133 six-cord groups (see Figure 2) is nearly equivalent to the number of tributaries (132) discussed in the 1670 revisita, and (2) when the knot values of the first pendant cord from each of the 133 six-cord groups are added together, their total closely matches the total tribute owed (367 pesos) mentioned in the revisita.

Figure 2. An example of a six-cord group patterning on khipus.

Moiety Affiliation and Pendant Cord Attachment

Later, in 2018, Manuel Medrano postulated that pendant cord attachment knots on the Santa Valley khipus may indicate the moiety affiliation (social half) of each tributary discussed in the 1670 revisita.[11] Moiety-based social organization was particularly prevalent during the reign of the Inka, continuing through the colonial era, and, in some places, persists even to this day. The two social halves in a moiety system—usually referred to in the Andes as hanan (upper, superior/primary) and hurin (lower, inferior/secondary)—are often composed of local ayllus. Generally, half of the ayllus belong to hanan and half to hurin. Additionally, ayllus are often ranked within each moiety, adding a secondary level of hierarchy.

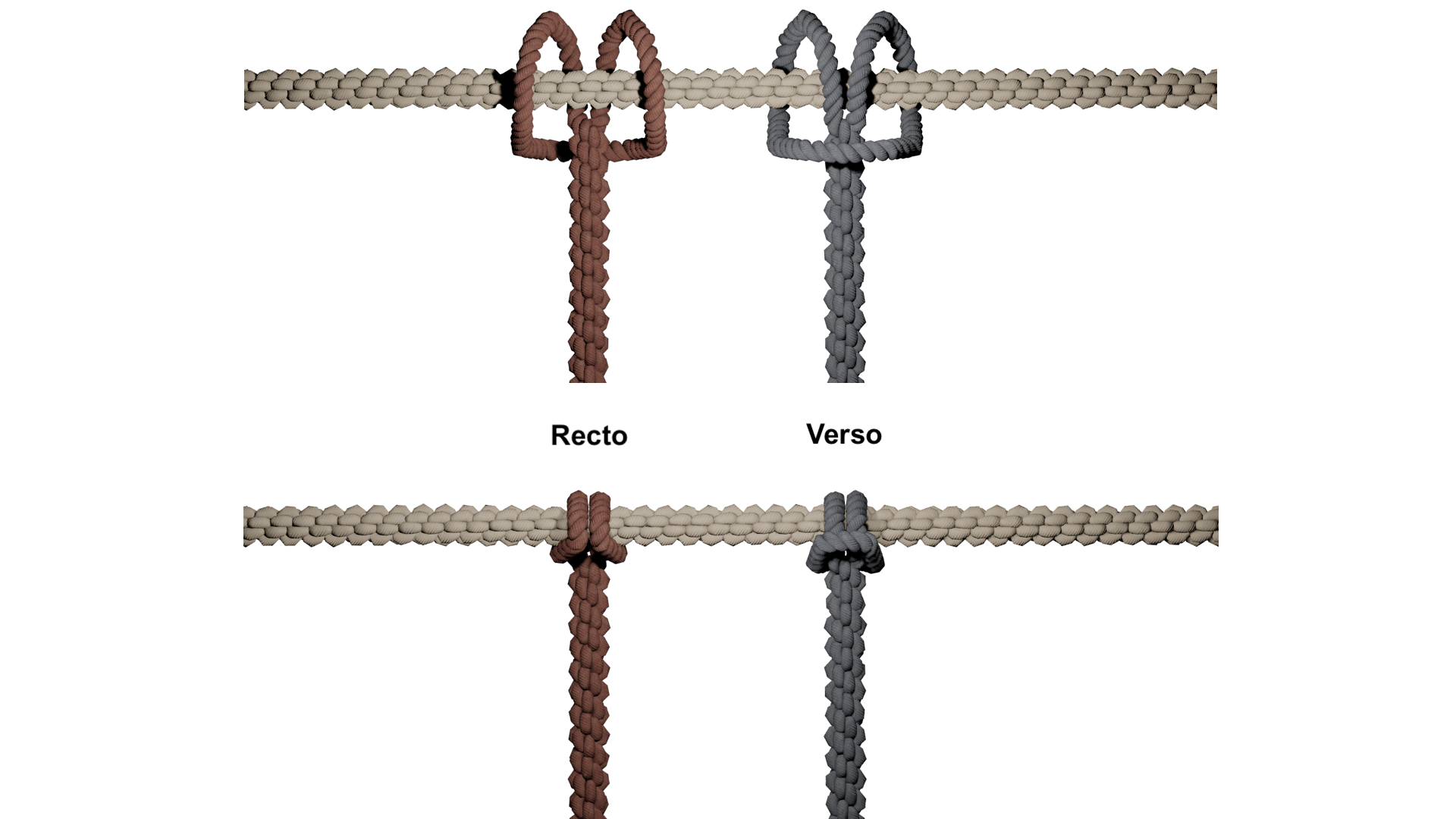

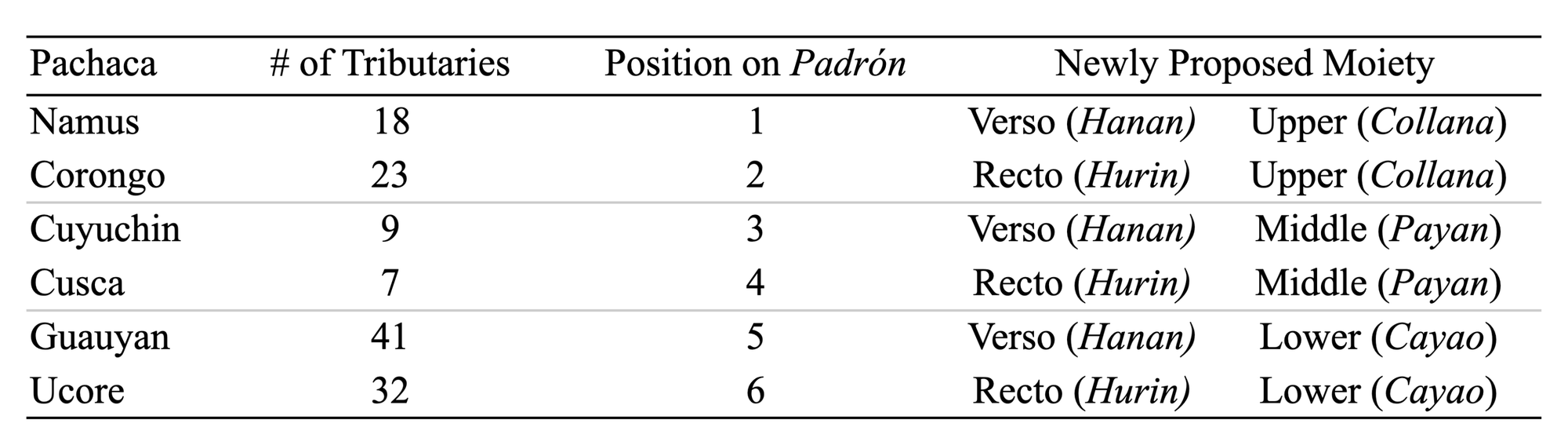

Medrano specifically observed that the two orientations of a typical pendant cord attachment knot used on khipus—often labeled as either “recto” or “verso” (Figure 3)—make it perfectly suited for recording binary information such as moiety affiliation. Using this hypothesis, Medrano found a total of 63 recto groups and 70 verso groups on the six Santa Valley khipus. He then separated the six pachacas from the 1670 revisita—named Namus, Corongo, Cuyuchin, Cusca, Guauyan, and Ucore—into proposed moieties. Based on the padrón from the 1670 revisita Namus contained 18 tributaries, Corongo 23, Cuyuchin 9, Cusca 7, Guauyan 41, and Ucore 32. Therefore, Medrano posited that the 70 verso groups were linked to the Corongo, Guauyan, and Cusca pachacas, whose named tributaries in the padrón total to 71, and that the 63 recto groups were linked to the Namus, Cuyuchin, and Ucore pachacas, whose named tributaries in the padrón total to 59.

Figure 3. Recto (left top and bottom) and verso (right top and bottom) pendant cord attachment knot orientations. The top example shows a “loosened” version of the knots, whereas the lower example depicts the attachment knots tightened against the primary cord.

Although this alignment produces moiety groupings that roughly match the proportions seen in the khipus, I was able to extend Medrano’s analysis and identify an alternative arrangement that fits the data more tightly. I published this revised alignment in the journal Ethnohistory in 2024, and the remainder of this post follows the argument laid out in that peer-reviewed article, “New Insights on Cord Attachment and Social Hierarchy in Six Khipus from the Santa Valley, Peru.”

In that study, I proposed a moiety alignment in which Namus, Cuyuchin, and Guauyan form a “verso” moiety, while Corongo, Cusca, and Ucore form a “recto” one. This revision matters for several reasons: (1) it produces the closest possible match to the known data; (2) it brings into view familiar bipartite/tripartite Andean hierarchies within the pachacas listed in the 1670 revisita; and (3) it allows us not only to group pachacas into moieties, as Medrano initially suggested, but also to propose to which moiety—hanan (upper) or hurin (lower)—each belonged. This, in turn, leads to a working decipherment of how verso and recto attachments signaled moiety affiliation in the six Santa Valley khipus.

Taken together, these observations make it possible to reconstruct a secondary layer of social hierarchy: the internal ranking of the six pachacas of 1670 San Pedro de Corongo (Table 1).

Table 1. Padrón position compared to FitzPatrick’s (2024) newly proposed moiety and number of tributaries.

A Familiar Bipartite and Tripartite Hierarchy

Bipartite/tripartite models, like the one found in Table 1, can also be seen in Quechua linguistics. Take the number six (suqta) for instance. Aside from suqta, the number six may also be referenced as kinsa kinsa (three plus three) or iskay kinsa (two times three). The separation of the six pachacas into two sets of three, via “verso” and “recto” moiety affiliations, echos the bipartite notion of kinsa kinsa (three plus three), whereas the pairing of reciprocal “verso” and “recto” pachacas parallels the tripartite notion of iskay kinsa (two times three).

Additionally, social and political bipartite/tripartite organizations were common under Inka rule. In fact, the pachaca divisions theorized above are reminiscent of Inka social structures illustrated by Tom Zuidema, who noted several nested bipartite/tripartite divisions in his outline of the ceque system. He argued that the city of Cuzco was divided into hanan and hurin halves, with each half being made of two other ranked halves. These inner halves, or quarters, were then further divided into three ranked parts labeled Collana, Payan, Cayao. For Zuidema, this tripartite division corresponded to a social hierarchy, with Collana on the top, Payan in the middle, and Cayao at the bottom.[12]

With a bipartite/tripartite structure proposed for the six pachacas, we can now theorize which moiety—hanan or hurin—each belonged to, and which pendant cord attachment type—verso or recto—encoded those divisions. To do so, it is useful to review the linguistics concept of markedness, developed by Roman Jakobson and Nikolai Trubetzkoy. Markedness refers to asymmetric binary oppositions in which one member of a pair is the unmarked, general, or default category, and the other is the marked, more restricted category. In English, for instance, “day” (unmarked) can refer to daylight or a full 24-hour period, whereas “night” (marked) refers only to darkness. A similar asymmetry appears in Quechua word pairs such as khallu (unmarked, meaning “one alone”) and khalluntin (marked, meaing “the one together with its mate”).

Khipu scholars have long applied markedness theory to Inka-style khipus, identifying several binary structures—S/Z knotting, S/Z plying, recto/verso attachments, and color-band opposition. Of these, recto versus verso attachments remain the only binary sign whose hierarchical relationship has not yet been deciphered.

However, taken together, the patterns above suggest that the six Santa Valley khipus use verso attachments to denote the unmarked, principal category, and recto attachments to denote the marked, secondary one. Thus, a verso attached cord likely signaled membership in the hanan (upper, unmarked) moiety, whereas a recto attachment signaled membership in the hurin (lower, marked) moiety. In short:

Verso = Unmarked = Hanan = Upper Moiety = Primary

Recto = Marked = Hurin = Lower Moiety = Secondary

Uneven Tribute and Local Negotiation

Additionally, the khipus may reveal an asymmetrical distribution of the actual tribute paid by each moiety—something the 1670 colonial record never mentioned. The knots on the six khipus suggest that members of the “verso” moiety paid far more—about 381 pesos in total, averaging 5.45 pesos per person—while the “recto” moiety paid only about 86 pesos total, or roughly 1.4 pesos per person. This uneven split could hint that the two groups may have negotiated how to divide the tribute among themselves, a local arrangement the Spanish scribe either did not know about or did not bother to record.

Other Evidence for the Proposed Moiety Divisions

Notably, his newly proposed hanan/verso (unmarked) and hurin/recto (marked) alignment appears to be reinforced by the tassels, or kaytes, on khipus KH0327 and KH0323. Sabine Hyland has argued that kaytes may indicate khipu genre and noted parallels between the yellow-orange kayte on KH0323 and one on a 1930s labor-accounting khipu.[13] But the kaytes on the Santa Valley khipus may also help encode moiety affiliation. KH0327, composed only of verso cords, has a single pale yellow tassel; KH0323, composed only of recto cords, has a pale-yellow and orange tassel. Thus, if the yellow tassel on KH0327 denotes the unmarked hanan category, then the addition of orange fibers on KH0323 serves to mark it as hurin (Figure 4). Similar to how adding the suffix “-ntin” to khallu transforms it from an unmarked to a marked word (i.e. khalluntin), the yellow tassel may be viewed as signaling an unmarked category, whereas the addition of orange to the tassel may transform it to signal a marked category. This reading also aligns with Jon Clindaniel’s findings on color ranking in khipus, with solid light colors as least marked and mixed or light–dark combinations as more marked.[14] The kaytes on these two khipus therefore may denote both their tributary genre and their moiety affiliation.

Figure 4. The pale-yellow and orange tassel found on KH0323 (Photo by Mackinley FitzPatrick).

Dating the Santa Valley Khipus

Interestinly, radiocarbon dates taken from the six Santa Valley khipus suggest that they may pre-date the 1670 revisita.[15][16][17] Rather than jettisoning the Santa Valley khipus from discussions of the 1670 revisita, taking the earlier radiocarbon dates at face value could instead indicate a pattern of khipu re-use. It is also possible that the six Santa Valley khipus may record an earlier iteration of tributary collection from the people of San Pedro de Corongo. This hypothesis could also help to explain any small discrepancies between the 1670 document and the set of six khipus.

Notably, some physical features on the six khipus support these hypotheses of reuse. Take, for instance, the presence of unknotted cords found on at least two of the Santa Valley khipus, KH0327 and KH0323. If color-banded khipus represent individual-level data, one would expect these khipus to have the most dynamic uselives. Consequently, untied knots may be used as a proxy for these low-level “working” khipus,[18] and again, this pattern is known ethnographically from early twentieth-century khipu practices in Anchucaya, Peru, where each year “the knots on the khipus were untied so that the khipus could be re-used”.[19] Moreover, unknotted cords on color-banded khipus are not exclusive to the Santa Valley khipus—e.g., color-banded khipu PC.WBC.2016.071 at the Dumbarton Oaks Museum. Additionally, the six khipus' original owner, Carlo Radicati di Primeglio, described encountering many unattached pre-made pendant cords as he laid out the six khipus for the very first time.[20] These pre-made cords may suggest a more dynamic life cycle for the six khipus, in which they were actively being updated, likely with the most recent tribute information. Thus, the unknotted cords on the Santa Valley khipus, in tandem with the many unattached pre-made pendant cords encountered by Radicati, suggests that these khipus were used for an extended period of time before finally being encoded with information strikingly similar to that described in the 1670 colonial document.

Conclusions

The enrichment of the 1670 colonial document by means of six Inka-style khipu presents a unique case, one in which the study of Indigenous records (i.e., khipu) can be used to inform a colonial document—and, in the process, our understanding of Indigenous practices, lifeways, and social hierarchies. The once simple list of tributaries on the 1670 revisita may now be enriched by notions of complex social hierarchies, nuanced by local tribute payment agreements and negotiations.

Continued work on the Santa Valley khipus should prompt renewed searches for related colonial documents and more research into colonial-era change in the region. The match is not perfect—complicated by small data discrepancies and the radiocarbon dates—but until better candidates emerge, the six Santa Valley khipus and the 1670 revisita of San Pedro de Corongo remain one of the strongest opportunities we have for advancing the interpretation of khipu signs.

Lettera apologetica was inspired by Lettere d'una peruana (Letters from a Peruvian Woman), a novel published a few years earlier. ↩︎

Hyland, Sabine, Sarah Bennison, and William P. Hyland. 2021. “Khipus, Khipu Boards, and Sacred Texts: Toward a Philology of Andean Knotted Cords.” Latin American Research Review 56 (2): 400–416. ↩︎

Pärssinen, Martti, and Jukka Kiviharju. 2004. Textos andinos: Corpus de textos khipu incaicos y coloniales. Tomo I. ↩︎

Pärssinen, Martti, and Jukka Kiviharju. 2010. Textos Andinos: Corpus de Textos Khipu Incaicos y Coloniales. Tomo II. ↩︎

Medrano, Manuel. 2021. “Khipu Transcription Typologies: A Corpus-Based Study of the Textos Andinos.” Ethnohistory 68 (2): 311–41. ↩︎

Uhle, Max. 1897. “A Modern Kipu from Cutusuma, Bolivia.” Bulletin of the Free Museum of Science and Art Ofthe University of Pennsylvania 1 (2): 51–63. ↩︎

Mackey, Carol J. 1970. “Knot Records in Ancient and Modern Peru.” PhD dissertation, University of California, Berkeley. https://www.proquest.com/docview/302394958/citation/9D21F602F03C4A46PQ/1. ↩︎

Urton, Gary. 2011. “Tying the Archive in Knots, or: Dying to Get into the Archive in Ancient Peru.” Journal of the Society of Archivists (ABINGDON) 32 (1): 5–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/00379816.2011.563100. ↩︎

Zevallos Quiñones, Jorge. 1991. “Padrón de Indios Tributarios Recuayes: Conchucos 1670.” In Etnohistoria Del Área Viru Santa: Un Avance Documental (Siglos XVI—XIX). Instituto Departamental de Cultura—La Libertad, Direccion de Patrimonio Cultural Monumental de la Nación, Proyecto Especial de Irrigacion Chavimochic. ↩︎

Urton, Gary. 2017. Inka History in Knots: Reading Khipus as Primary Sources. University of Texas Press. ↩︎

Medrano, Manuel, and Gary Urton. 2018. “Toward the Decipherment of a Set of Mid-Colonial Khipus from the Santa Valley, Coastal Peru.” Ethnohistory 65 (1): 1–23. ↩︎

Zuidema, Reiner Tom. 1964. The Ceque System of Cuzco: The Social Organization of the Capital of the Inca. Vol. 50. Brill Archive. ↩︎

Hyland, Sabine. 2020. “Subject Indicators and the Decipherment of Genre on Andean Khipus.” Anthropological Linguistics 62 (2): 137–58. https://doi.org/10.1353/anl.2020.0004. ↩︎

Clindaniel, Jon. 2019. “Toward a Grammar of the Inka Khipu: Investigating the Production of Non-Numerical Signs.” PhD dissertation, Department of Anthropology, Harvard University. ↩︎

Cherkinsky, Alexander, and Gary Urton. 2014. “Radiocarbon Chronology of Andean Khipus.” Open Journal of Archaeometry 2 (1): 32–36. ↩︎

Ghezzi, Ivan, Manuel Medrano, Alcides Alvarez, et al. 2023. “Refining Khipu Absolute Chronology via Bayesian Modeling: New Evidence from the Santa Valley.” Symmetry, Repetition, and Pattern Recognition in Andean Khipus, Boundary End Archaeology Research Center, August 10. ↩︎

“Khipus and Written Documents.” Google Arts & Culture. https://artsandculture.google.com/story/TwURueXdUOqKzA. ↩︎

Medrano, Manuel, and Ashok Khosla. 2024. “How Can Data Science Contribute to Understanding the Khipu Code?” Latin American Antiquity, May 6, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1017/laq.2024.5. ↩︎

Hyland, Sabine. 2016. “How Khipus Indicated Labour Contributions in an Andean Village: An Explanation of Colour Banding, Seriation and Ethnocategories.” Journal of Material Culture 21 (4): 490–509. ↩︎

Radicati di Primeglio, Carlos. 2006. Estudios sobre los quipus. 1a ed. Edited by Gary Urton. Serie Clásicos sanmarquinos. Fondo Editorial Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos. ↩︎

Comments ()