An Underrecognized Doctoral Thesis on Inka Khipus: Antonia Molina Muntó, 1975

As in many academic fields, unpublished PhD dissertations on khipus can be difficult to locate and are largely underrecognized. Anthropologist Carol Mackey’s “Knot Records in Ancient and Modern Peru” (1970) is perhaps the best known, though it is not the only one—nor the first—of its kind. Carlos Radicati di Primeglio’s “Sobre seis quipus del antiguo Perú” (1952) is the earliest example listed in a 2014 inventory of khipu-related works.[1] The years since 2014 have brought a flurry of PhD dissertations on khipus—at least ten, by my count.[2]

In addition to recognizing these varied and exciting projects, this post seeks to recover and highlight a much earlier study. On June 12, 1975, Antonia Molina Muntó defended “Origen, función y finalidad de la escritura peruana en cuerda y nudos. El quipu,” a doctoral thesis submitted to the Faculty of Arts at the Universidad Complutense de Madrid.[3] In it, she presents a detailed synthesis of colonial-era chronicles as well as an original study of 26 Inka-style khipus held in the Berlin Ethnological Museum. The thesis is rarely cited, in part because it can only be consulted by prior appointment at the Complutense University’s Biblioteca Histórica.[4] I had the opportunity to do so during a research visit to Madrid in 2022, and I am pleased to share here a summary of Molina Muntó’s dissertation along with some brief reflections on its place in the history of khipu research.

The dissertation’s table of contents reads as follows:

Introducción

Prólogo

Fuentes utilizadas

Bibliografía crítica

HipótesisParte primera. La cultura incaica y su relación con el tema

Cap. 1o – Organización administrativa incaica. Economía, tributos y hacienda.Parte segunda. El quipu

Cap. 2o – Los orígenes: a) noticias de los cronistas; b) su interpretación.

Cap. 3o – Interpretaciones y opinión de los especialistas. Numérica, instrumentos nemotécnicos y escritura.

Cap. 4o – Descripción del quipu. Administrativas, fiscales, estadísticas y narrativas. (Different title in body of dissertation: Descripción del quipu. Clasificación y características.)

Cap. 5o – Funciones del quipu. Administrativas, fiscales, estadísticas y narrativas.

Cap. 6o – Los quipucamayos.

Cap. 7o – Los quipus modernos.Parte tercera

Cap. 8o – Catalogación de los principales quipus conocidos.

Cap. 9o – Los quipus del Museum für Völkerkunde de Berlín.Conclusiones

Notas

Bibliografía

Apéndices instrumentales

Over some 400 pages, Molina Muntó contends that Inka khipus were not merely a “perfect system of accounting,” but also a “true system of written expression—that is, writing—since [they] served as a means of communication and transmission of ideas, through a code possessed only by the initiates, the quipucamayos.”[5] She argues that khipus were not phonetic (recording speech sounds) but ideographic, representing objects and concepts directly without reliance on any particular language.

The rest of the dissertation provides support for this claim through a combination of textual and material evidence. In the first category are works by various colonial-era chroniclers, which, according to Molina Muntó, make specific claims about the existence of ideographic khipus. In her reading (chap. 2), the chronicles defend two positions: that khipus are accounting instruments, and that they are a form of “true” writing. From this, she derives a threefold classification of Inka khipus: (1) accounting and statistical khipus; (2) “mnemotechnical” (memory-aid) khipus; and (3) ideographic khipus. This typology, Molina Muntó notes, aligns with that proposed by Carlos Radicati di Primeglio a decade earlier.[6]

Following this are detailed discussions of each khipu type (chap. 3), which, for types (1) and (2), largely survey earlier analyses by Radicati and L. Leland Locke.[7] It is in her description of ideographic khipus (type 3) that Molina Muntó’s own conclusions from the material record emerge. She presents a mathematical calculation: with just six cords and four available colors, a khipukamayuq would have been able to encode 2,376 ideograms—already enough for a limited vocabulary. Extending this logic to actual khipus, with their impressive variety of colors and knots, would have permitted an “innumerable” quantity of signs—in short, a true writing system.[8]

The remaining chapters search for examples of this complexity in surviving khipus while reconstructing khipu use in the Inka-era Andes. Molina Muntó emphasizes khipus’ variability (chap. 4), noting their different pendant lengths, the presence of top cords, subsidiary cords with different kinds of attachment knots, a diverse array of colors, and even examples of khipus with multiple primary cords tied together.[9] Those tasked with learning the manifold combinations of khipu colors and knots were high-status individuals (chap. 6), who wielded khipus with such dexterity that more mundane, daily uses of khipus for accounting would have presented little challenge in comparison (chap. 5). Molina Muntó then turns to twentieth-century examples to suggest parallels with ancient khipus, surveying earlier work on herding khipus by Peruvian anthropologist Óscar Núñez del Prado (chap. 7).[10] Like many of her contemporaries, Molina Muntó understood modern khipus to be a reduced, simplified form (una degeneración) of their Inka equivalents.[11] Chapter 8 provides a 30-page description of 12 khipus: eleven previously studied by Andrés Radamés Altieri in an Argentine private collection, and one published by Molina Muntó in 1966 from the Museo de América in Madrid.[12]

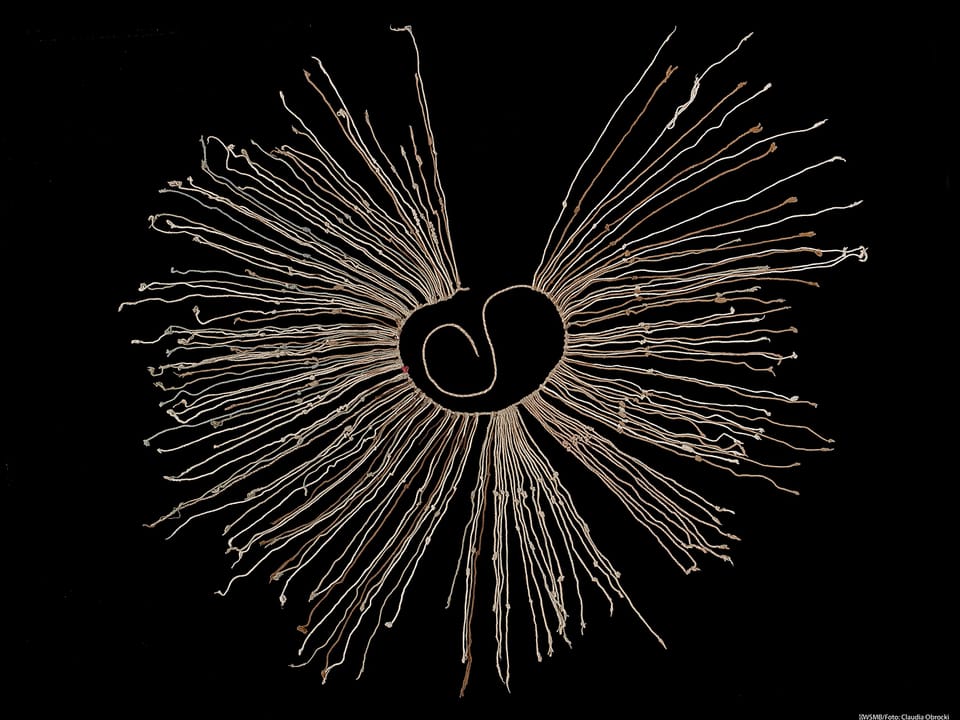

The final chapter is the dissertation’s longest (almost 240 pages) and presents detailed comments and cord-by-cord data tables for 26 khipus in the collections of the Berlin Ethnological Museum. Her introduction to them warrants reproduction in full:

We present a study of 26 khipus preserved in the Museum für Völkerkunde, Berlin, which possesses a magnificent collection of more than 300 specimens. The khipus examined in our study are made of cotton. They are beautiful examples, made with great care. In general, they are well preserved, although in some of them the passage of time has left its mark—some cords are cut, broken, or faded—yet this in no way diminishes their value for a fruitful study. We cannot dismiss any specimen, no matter how deteriorated it may be.[13]

Molina Muntó’s selection of khipus appears to have prioritized examples containing at least several dozen pendant cords. I summarize her observations—including what I regard as her especially notable remarks—in the table below. I reproduce her assigned khipu numbers, museum accession numbers, and provenance information as stated in the dissertation.

| Khipu # | Accession # | Reported Provenance | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | VA 42554 | Pachacamac | 101 pendants in 15 groups; the first pendant in almost every group is blue (p. 163). |

| 2 | VA 47079 | Ica | 219 pendants in 20 groups; all even-numbered pendant groups have no knots or subsidiary cords, while the odd-numbered groups do (p. 166). |

| 3 | VA 63040 | Huacho | 131 pendants in 45 groups. |

| 4 | VA 42607 | Pachacamac | Multiple primary cords tied together (p. 172). |

| 5 | VA 47070 | Ica | 66 pendants in 8 groups. |

| 6 | VA 16145 | Ica | Multiple primary cords; some subsidiary cords have “double” figure-eight knots (pp. 178–179). |

| 7 | VA 42517 | Pachacamac | 33 pendants in 4 groups; especially long pendant cords (p. 181). |

| 8 | VA 47076 | Ica | 80 pendants in 24 groups; high frequency of blue in this khipu (p. 184). |

| 9 | VA 42535 | Pachacamac | 64 pendants in 31 groups; repeated seriation of colors on alternating cord groups (p. 186). |

| 10 | VA 42526 | Pachacamac | 48 pendants in 16 groups. |

| 11 | VA 42513 | Pachacamac | 194 pendants in 14 groups; occasional figure-eight knot below long knot on same cord; double long knot in group IX. |

| 12 | VA 63044 | Nazca? | Four primary cords; especially colorful khipu, with 27 reported colors (p. 193). |

| 13 | VA 42553 | Pachacamac | 64 pendants in 4 groups; pendant 58 has a nudo de ojal, which, in the associated diagram, appears to be two adjacent pendants tied to each other (p. 194). |

| 14 | VA 42560 | Pachacamac | 32 pendants in 10 groups. |

| 15 | VA 47091 | Ica | 55 pendants in 6 groups. |

| 16 | VA 42528 | Pachacamac | 25 pendants in 4 groups (listed as groups 1 and 2 for each of parts A and B). |

| 17 | VA 42533 | Pachacamac | 86 pendants (+5 in khipu “part B”) in 9 groups. |

| 18 | VA 16136 | Ica | 80 pendants in 15 groups; reports a “parallelism” in knot presence/absence, such that cords of the same color tend to have knots present or absent in the same locations (p. 201). |

| 19 | VA 42597 | Pachacamac | Reports 2 kaytes (affixed bundles), one of which appears at the intersection of two primary cords (p. 202); includes detailed drawings of the kaytes. |

| 20 | VA 16140 | Ica | 161 pendants in 15 groups. |

| 21 | VA 42564 | Pachacamac | 57 pendants in 14 groups. |

| 22 | VA 42516 | Pachacamac | 109 pendants in 11 groups. |

| 23 | VA 42510 | Pachacamac | 141 pendants in 15 groups; pendant #7 in group III appears to have a figure-eight knot in the tens’ place, above a 6L knot in the ones’ place. |

| 24 | VA 42538 | Pachacamac | 276 pendants in 11 groups. |

| 25 | VA 22574 | Chancay | 135 pendants; reports 23 distinct colors, with a high frequency of blues and greens; subsidiary cords attached at quite different heights on the pendant cords (p. 215). |

| 26 | VA 42556 | Pachacamac | 74 pendants in 3 groups; blues and greens reported (p. 216). |

Volume I contains each khipu’s entry and associated data table, while the fold-out diagrams are bound together in vol. II. The latter are visually reminiscent of the khipu diagrams produced in the 1920s by Swedish anthropologist Erland Nordenskiöld.[14] Molina Muntó’s diagrams are drawn in black pen on light-pink graph paper, without cord-by-cord color information. The distance between cord groups and the length of individual cords are not drawn to scale. Subsidiary cords branch off at right angles from the pendant cords to which they are attached.

The diagrams fill most of vol. II, which also includes facsimile folios of texts by Martín de Murúa, Pedro de Cieza de León, and Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala; photographs of khipus held in Madrid, Buenos Aires, Lima, and Basel; and three close-up images of khipu pendant cords in varying states of preservation.

The final pages of Molina Muntó’s dissertation return to her combinatorial proofs. Expanding her earlier thought experiment to allow for seven different cord colors, their combinations, and knots arranged in up to four clusters per cord, she concludes that any given khipu cord could take on at least 1,653,372 distinct forms.[15] Based on her study of the khipus in Berlin, which sometimes present pendant groups of varying sizes, this estimate would increase “prodigiously” (de forma prodigiosa) when applied to actual specimens.[16] Ultimately, Molina Muntó concludes, such combinatorial capacity would have enabled Inka khipukamayuqs to record ideograms of all sorts using different arrangements of colors, knots, and cord groupings. Khipus were, in her view, a form of writing.

Where does Molina Muntó’s dissertation fit in the long arc of khipu research? From a decipherment perspective, the ideographic hypothesis no longer plays a significant role in decoding efforts. Expanded cataloging and data-science work have proposed more straightforward numerical interpretations for the types of khipus that Molina Muntó and Carlos Radicati di Primeglio conjectured might contain non-numerical ideograms.[17] Molina Muntó’s data tables omit several khipu characteristics typically recorded today, including attachment-knot direction, cord twist, knot directionality, and pendant-cord termination type. Nonetheless, her detailed recordings provide a crucial 1970s snapshot of the khipus in Berlin, which holds the world’s largest such collection. These recordings should be revisited and compared with the data in the Khipu Field Guide, particularly in relation to colors, which can change substantially over time due to degradation, exposure to light, and wear. As Karen Thompson demonstrates in recent work, multiple readings of the same khipu can fill gaps left by individual researchers, producing a kind of composite image.[18]

From the historian’s perspective, Molina Muntó’s 1975 dissertation was the largest single-collection khipu research project completed since L. Leland Locke’s work in the 1910s at the American Museum of Natural History. The hundreds of pages of data tables and diagrams she produced constituted the largest compilation of its kind to that point, anticipating the publication of Marcia and Robert Ascher’s first Code of the Quipu Databook three years later.[19] Diverging from Erland Nordenskiöld’s long-influential theory of khipus as astronomical talismans, Molina Muntó affirmed their complexity and capacity for meaningful expression, based on specific features she observed during countless hours spent working over cordage in a Berlin-area storage room. Although her theories are no longer widely accepted, the process by which she arrived at them deserves attention from historians of Andean archaeology and archaeological decipherment. That, of course, is a story still to be written.

Rubén Urbizagástegui Alvarado, La escritura inca. Quipus, yupanas y tocapus (Hipocampo Editores, 2014), https://www.researchgate.net/publication/345747619_la_Escritura_Inca_Quipus_yupanas_y_tocapus. ↩︎

These include, in chronological order: Molly Tun, “El quipu. Escritura andina en las redes informáticas incaicas y coloniales” (University of Minnesota, 2015); Jon Clindaniel, “Toward a Grammar of the Inka Khipu: Investigating the Production of Non-numerical Signs” (Harvard University, 2019); Mónica Medelius, “Dando cuentas. Los quipucamayos en las comunidades indígenas y ante la administración colonial” (Universidad Pablo de Olavide, 2020); Magdalena Setlak, “Hacia una lexicografía de los quipus. Estudio etnohistórico sobre la función y contenido del sistema andino de registros de la información mediante cuerdas y nudos” (Universidad Complutense de Madrid, 2022); Maria Koulouri, “Deciphering the Multilevel Khipu Structures: A Mixed-Methods Triangulation Modelled on the Communal Khipu Boards of Mangas and Casta” (University of St Andrews, 2023); Andrés Chirinos, “Organización politico-territorial en el Perú central del siglo XVI. Un estudio por medio de análisis espaciales SIG y textos-quipu como fuentes” (UNED, 2024); and Lucrezia Milillo’s PhD thesis (University of St Andrews, 2025), as well as khipu dissertations in progress by Mackinley FitzPatrick (Harvard University), Andras Stribik (University of St Andrews), and the present author. ↩︎

I first learned of Molina Muntó’s thesis from a brief excerpt published in the same year: Antonia Molina Muntó, “Origen, función y finalidad de la escritura peruana en cuerda y nudos. El quipu” (excerpt from PhD diss., Universidad Complutense de Madrid, 1975). It reports that the thesis, written under the supervision of Spanish historian and anthropologist Manuel Ballesteros Gaibrois, received the grade of ‘outstanding’ (sobresaliente), cum laude. ↩︎

The thesis is bound in two volumes, both under call number T 24157; see https://ucm.on.worldcat.org/oclc/914555717. Photographs were not permitted in the reading room as of my 2022 visit. ↩︎

“Un auténtico sistema de expresión escrita, es decir de escritura, ya que servía de medio de comunicación y transmisión de ideas, por medio de una clave [en] cuya posesión se encontraban únicamente los iniciados—quipucamayos.” Antonia Molina Muntó, “Origen, función y finalidad de la escritura peruana en cuerda y nudos. El quipu” (PhD diss., Universidad Complutense de Madrid, 1975), viii. ↩︎

Carlos Radicati di Primeglio, La “seriación” como posible clave para descifrar los quipus extranumerales (Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, 1964). ↩︎

L. Leland Locke, The Ancient Quipu or Peruvian Knot Record (American Museum of Natural History, 1923). ↩︎

Molina Muntó, 77, 82. ↩︎

Molina Muntó states that she is the first to systematically describe a khipu with multiple primary cords (ibid., 88). ↩︎

Óscar Núñez del Prado, “El khipu moderno,” in Q’ero. El último ayllu inka, 2nd ed., ed. Jorge Flores Ochoa et al. (1950; 2nd ed., Instituto Nacional de Cultura and Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, 2005). ↩︎

Molina Muntó, 124. Work on Inka-era herding khipus has reduced the influence of this view: Galen Brokaw, A History of the Khipu (Cambridge University Press, 2010). ↩︎

Radamés A. Altieri, “Sobre 11 antiguos Kipu peruanos,” Revista del Instituto de Antropología de la Universidad Nacional de Tucumán 2, no. 8 (1941): 177–211; Antonia Molina Muntó, “El quipu de Madrid,” in Actas y Memorias, XXXVI Congreso Internacional de Americanistas, vol. 1 (ECESA, 1966). It does not appear that Molina Muntó examined the khipus in Argentina firsthand. ↩︎

“Presentamos un estudio de 26 quipus conservados en el Museum für Völkerkunde de Berlín, que posee una magnífica colección de más de 300 ejemplares. Los quipus objeto de nuestro estudio están confeccionados en algodón. Se trata de hermosos ejemplares fabricados con mucho esmero. Generalmente se conservan en buen estado, aunque en algunos de ellos el paso del tiempo ha dejado sus huellas, y tienen algunas cuerdas cortadas, rotas o desteñidas, cosa que no les resta en absoluto valor para un estudio provechoso, y no podemos desdeñar ningún ejemplar por muy deteriorado que se encuentre.” Molina Muntó, “Origen, función y finalidad de la escritura peruana en cuerda y nudos,” 162. ↩︎

Erland Nordenskiöld, The Secret of the Peruvian Quipus (Elanders, 1925); idem, Calculations with Years and Months in the Peruvian Quipus (Elanders, 1925). ↩︎

Molina Muntó, “Origen, función y finalidad de la escritura peruana en cuerda y nudos,” 403. ↩︎

Ibid. ↩︎

Manuel Medrano and Ashok Khosla, “How Can Data Science Contribute to Understanding the Khipu Code?” Latin American Antiquity 36, no. 2 (2025): 497–516, https://doi.org/10.1017/laq.2024.5. ↩︎

Karen M. Thompson, “A Numerical Connection Between Two Khipus,” Ñawpa Pacha 45, no. 1 (2025): 83–104, https://doi.org/10.1080/00776297.2024.2411789. ↩︎

Marcia Ascher and Robert Ascher, Code of the Quipu Databook (University Microfilms, 1978). ↩︎

Comments ()