A Numerical Connection Between Two Khipus: An Informal Description

By way of introduction, I am a mathematician and data-lover and maker who, when growing up, also wanted to be an archaeologist and an art/ist teacher and an architect.

I had long been fascinated by khipus before I first heard about The Khipu Field Guide (KFG) while listening to the ArcheoEd podcast khipu episode in 2023. In a moment of shining confidence, I reached out to Ashok to learn more.

My first project was to check the data in the KFG for the khipus recorded in the 1970–80s by Marcia and Robert Ascher. I feel a kind of kinship with Marcia, as she was an ethnomathematician, and I can see in her work that we may have thought in similar ways. Together with Robert, an anthropologist, they formally collected characterization data from 215 khipus.

This data was published in three separate documents.[1] My assignment was to check that the information in the KFG digital data reflected what was in these documents, and to make corrections where necessary. This may seem like a horrible task to many, but this kind of data-work is satisfying for me, because reliable data is critical for any subsequent analysis and knowledge-building.

While I was finishing up this work, I realized that over the decades some khipus had been recorded by more than one researcher. I wondered how this might show up in differences in the data.

I was particularly enamored by a complex khipu – #780 at the Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino, in Santiago, coded AS70 by the Aschers and now usually referred to as KH0083 (fig.2).[2] It had the same marker cords, with a small strong red element, as khipu AS69 / KH0082 (fig.1), which is the largest khipu yet found at over 3m long with more than 1800 cords. These two khipus were said to have been found together.

I embarked on some numerical play, looking at the data for each khipu, wondering if they may be related because that red/white cord acted as a delineator of some kind. I had no goal, no aim, just curiosity and wonder, and a willingness to be led by the data, for I was still very new to khipu data.

A pattern emerged: KH0082 was divided into ten parts by the red/white marker cords, and the pendant cords were organized into clusters of seven cords each (give or take) between these markers; KH0083 had seven clusters each with ten cords, alongside an eighth unusual cluster of cords. Eventually I found a connection – the values within this pattern of tens and sevens lined up.

I have written about this numeric connection in an academic journal article,[3] and I have been looking forward to writing about it in a less formal way.

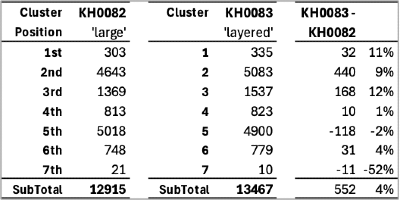

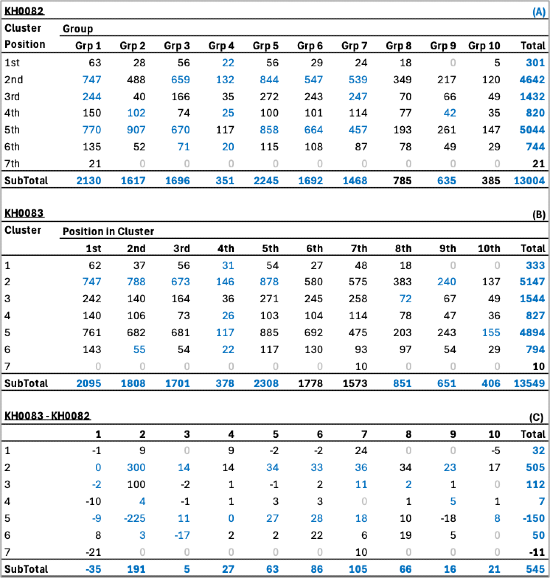

When I look at the first cord of each cluster in KH0082 (this is what I call cluster-position 1) and sum up the values on those cords, I get 303. When I add the values in the first cluster in KH0083, I get 335; it’s close but not exact.

Then, when I did that for each of the seven cluster-positions in KH0082 and compared that to each of the seven clusters in KH0083, there was a good match for magnitude (table 1; all numeric tables are at the end of the text, in case numbers are not your thing). I became more curious.

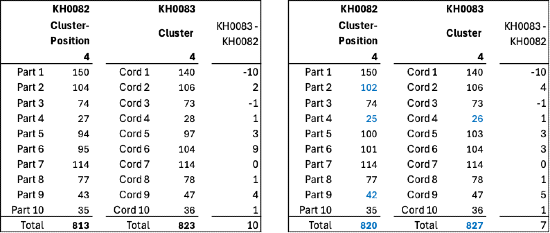

The match was closest for cluster-position (KH0082) and cluster 4 (KH0083) – 813 and 823 respectively – so I thought to start there. I wondered if there might be a finer alignment. If instead of taking the sum of cluster-position 4 across the whole khipu, what if I split it up by the parts as divided by the red/white marker – then I get ten values for KH0082. And then I could compare those values to the values in KH0083 for each cord, including the subsidiaries, in cluster 4 (left in table 2). Again, the numbers are not exact matches, but interestingly close.

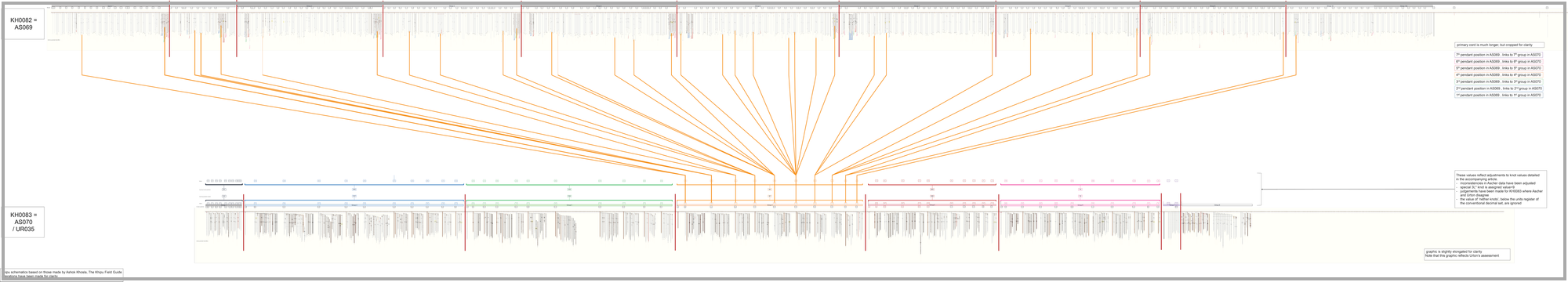

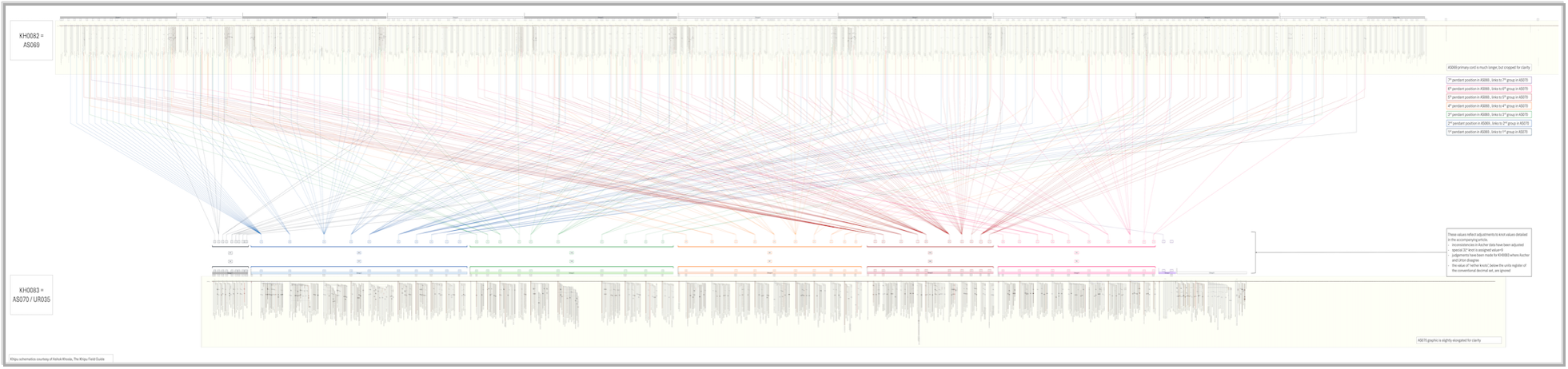

While I love numbers, I really need to visualize their relationship. I made the below diagram as a visual representation of the connections for position/cluster 4 (it is necessarily very detailed because there are lots of cords). Across the top of the graphic is the KFG schematic for KH0082, and across the bottom is KH0083. The red/white marker cords for each khipu are represented by red vertical lines overlaying the schematics, dividing each khipu into parts. The orange lines connect knotted cords in KH0082 (for clarity the blank cords are not marked) to their corresponding partner cord in KH0083. For example, each knotted cords in the fourth position in their cluster in part 1 in KH0082 (there are two) connect with cord 1 and its subsidiaries in part/cluster 4 in KH0083.

There are two other special features of these khipus. First, they both have a special knot type not seen anywhere else (so far). Second, they have knots added below what we would ordinarily consider the last ‘unit’ knot (ie. values for 1 to 9) on a cord. The relationship of some of the cords suggested that the special knot might be treated as value=9. And while there are debates about how to handle knots below the (presumed) unit knot register, one argument is that they represent a count that is not to be added nor subtracted but essentially treated entirely separately. When I reconsider the numbers for cluster 4 in this way, the values slightly change (right in table 2, the numbers in blue have changed).

Then, looking at each of the ten groups in this way (table 3), the numbers line up in a way that cannot be coincidental. It would of course be much more satisfying if the comparisons were exact across the board (more on this shortly).

The visualization of all these connections is a lot to take in. Follow this link to a zoomable version of it: https://doi.org/10.26188/26105248.

I have found it surprisingly difficult to condense this numerical connection into a single sentence. I did not really manage it in my paper last year, but I have had more time to talk about it since. Therefore, my latest attempt is this: KH0083 (AS70) looks to be an indexed sum and reallocation of KH0082 (AS69), with complex cord coloring playing a role we are yet to understand.

With respect to the inexact match, we must remember that we are working with objects that are old and fragile, and unless you have recorded a khipu yourself it is all too easy to underestimate how onerous the task is (I was humbled by this myself). Sometimes counting how many single knots there are, when they are all squished together, is surprisingly difficult. As such, differences of tens, and those less than ten, can be understandable. Or, of course, the khipus may have been in progress and not yet completed.

The smaller khipu, KH0083, is #780 at the Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino and is on display, so it could be revisited in the future to check the data. Sadly though, the larger khipu, KH0082, has been lost to the public record – as far as I understand, it was last seen in the 1970s or 80s. This means we cannot check the data for fidelity to the object, nor record the additional characteristics we now consider to be as meaningful as the knots. If you ever see a khipu, or even a fragment of a khipu, with marker cords with a small length of red at the top of a white cord, please do let me know!

This has been a retrospective and narrative description of what looks like it was a linear and simple thought process. But the experience was less rigid and partly iterative. I think of it as an example of small data methodology, in contrast to ‘big data’. To me, that means being attentive to each data element and undertaking a numeric analysis effectively ‘by hand’ (while I did use Excel, it was primarily a holding place for the data and a tool to make experimental selection and summation more rapid; I basically think in/with Excel!). While big data approaches have obvious advantages, there is definitely a valued place for small-scale, hand-held and hand-made, slow scholarship in the field of khipu research.

Numeric connections between khipus, like the one above, can bring us closer to understanding how the khipu-makers and their community employed this cord technology. It may even take us some way toward understanding what was important to them – for example, these two khipus appear to hold the same data, but it is split in different ways in each khipu, and it must have been meaningful to record the data in both ways (cords, and especially colored cords, are not materials to be wasted) – and how they conceived of and arranged their work or resources, or whatever it is that the knots record.

Numeric tables

Endnotes

- AS1–AS9: Ascher, Marcia and Robert Ascher. 1972. Numbers and Relations from Ancient Andean Quipus. Archive for History of Exact Sciences 8(4):288–320.

AS10–AS200: Ascher, Marcia, and Robert Ascher. 1978. Code of the Quipu: Databook. University Microfilms, Ann Arbor.

AS201–AS215: Ascher, Marcia, and Robert Ascher. 1988. Code of the Quipu: Databook II. University Microfilms, Ann Arbor, Michigan - For many decades researchers numbered the khipus they studied for their own reference. These codes made their way into the published literature, and were often prefaced by the experts’ initials, and this became a shorthand for others to refer to specific khipus. However, there is a critical argument that this kind of labelling of khipus inappropriately centres individual (often non-Indigenous) researcher at the expense of the nature of the original object while obscuring the fact that it was often a team involved in the recording labour. There is now a preference for using a more generalised ‘KH’ coding system (employing the kh at the beginning of the word khipu). For more details see: Brezine, Carrie J., Jon Clindaniel, Ian Ghezzi, Sabine Hyland, and Manuel Medrano. 2024. A New Naming Convention for Andean Khipus. Latin American Antiquity, 2024:1–6.

- It is important to note that not all khipu cords are believed to record numeric data. I will write more about this in the near future.

Publication: Thompson, Karen M., 2024. A Numerical Connection Between Two Khipus. Ñawpa Pacha, pp.1–22.

The contents of this acedemic article has also been covered in a piece I wrote for The Conversation.

Comments ()